FUTURE-MEDIEVAL

”The speed of

darkness” is seemingly the opposite to “the speed of light”. Darkness moulds

form, and extracts the light, giving a sense of time through shadow. It is

atmospheric space, the sort of place a romantic artist might set their easel.

So you might say it’s a place where calmness and ease of thought are in the

air, and the play of shadow gives a restful sense of time passing.

Now, you could

do without this space and instead inhabit a future “lightspace” (see first

post), but it seems to me that is just one future. There is no reason why the

speed of thought, of calmness and meditation, can’t be part of a future. It’s

just not the transhuman one of algorithms (see 2nd post).

Through a French

contact - one Perrine Sandrea - I got into French BD in the late 70s – the

golden age of Pilote and Metal Hurlant – and retrospectively

their alternate reality futures are mind-numbingly accurate in a crazed way.

Perrine Sandrea *

What I want to

do is to relate the medievalism of BWS’s prints to, specifically, Chantal

Montellier’s bold, shadow-haunted futurescapes. Dating from late 70s/80s, these

are the first and best noirish alternate futures.

There’s a lot

you could write about alternate futures – the crazed cityscapes of Caza, Bilal,

Motter, Schuitten and Gilbert Hernandez – but I want to focus on the simplicity

of Montellier’s black and white style. Despite all the futuristic complexity of

the militaristic, media-fixated Wonder City, it shares one thing in common with

its successors, something that probably originates with Le Corbusier’s ideal

template of the ‘30s.

This is

basically that all the noble idealism is so fantastically misguided that all

the crazed, Machiavelian scenes follow almost as a matter of course. The

idealism is essentially rational totalitarianism. What this says is that one

vision is sufficient for humanity to have ordered, satisfying existences.

Obviously the fallacy is so laughable that Montellier and the others have a

ball playing it out.

It’s an Apollonian

vision, brought to its peak in the aims of transhumanism. What happens in

Montellier is that the vision is constantly undercut by the simplicity of her style.

What you can say (from post 2) is that things are simplified by the use of

shadow. It’s a way of moulding the form, establishing solid geometry, bold

design and silhouette.

Montellier does

this because she wants to create mood and tension. Mood and tension are created

by the irresolvable contrast of black and white. What occurs is what occurs in

BWS’s harshly shaded figure drawing (mythical prints - post 1). A type of

visual symbolism that tells us the shadowland expresses mood, gives a sense of

time and geometrical space.

Mood is a

product of simplicity and an artist’s sense of refined delicacy. Comic book

artists are very good at this subtle undermining of a logical Apollonian

vision. Montellier seems to use Professor Nimbus as her Einstein substitute; a

universal expert with vision and advise for the citizenry.

Motter’s version

of this is Radiant City (Mr X), making the “lightspace” connection

obvious. It’s the very simplicity of shadow that makes it impenetrable to

logic, its mutability of form and changing expression. Artists, whether they

are aware or not, are subverting complexity with a world of shifting moods and

expressions.

This world is

actually the geometric world of time and space. Unlike Einsteinian space, which

is theoretical, Euclidian space is almost stage-lit. The stage-lit sense of

presence that you get in BWS’s prints is a nice riposte to a world which is so

tenuous and seemingly chasing fanciful theories, when the world of time and

space is there in bold outline.

And imagination,

because that’s what the world of time and space is. Because it’s not tenuous or

fanciful, because it’s a simple, bold reality, it affects us and we are

moulded, inculcated. We can dream. The shadowland – another word for Euclidean

– is the world of romantic decadence, or heroic romance. Of gardens which

absorb light, that need water, oases, the picturesque days of yore.

Another artist I

became familiar with was Italian Hugo Pratt, creator of romantic seafarer Corto

Maltese. His use of line is subtle and intense. In A Ouest de l’Eden (Pilote

#52, 1978), the dividing line between light and shade in the desert almost

seems to shimmer with the sun, moving, you can imagine, with the passage of

day.

The passage of

time, trecking to an oasis, dreamlike images that affect the mind. Shadows that

mould things that are in time and place, transport us also across time. This is

an alternate reality to the tenuous theories of “Professor Nimbus”. The

imagination has free rein and, in the words of Grace Slick’s “Hyperdrive”, we

can

Think

ourselves light years ahead

Or put

yourself 1,000 years back in time

Despite what

“Nimbus” says, things are actually simple, and there is a purely pictorial

aspect that transports us across time. What we respond to are drama, graphic

and sculptural qualities.

These images

affect us because the energy of line is irresolvable. It’s always a balance of

opposing forces, like Newton’s action and reaction. This happens in a world –

an alternate reality – where the energy of shadow counterbalances light. Shadow

is the diminution or extinction of light and that gives us geometric shape,

sense of time.

Now, you could

do without that world, and you’d be worshipping at the shrine of E=MC². But the

point is that is the light equation; not everything is light. There are two

aspects to reality and one is simply lack of light or night. You can say that

is less important, but the entire span of history and prehistory is against you

It is equally

important, and together they are irresolvable. Artists, by their use of line,

are establishing mood and atmosphere by the use of contrast. They don’t exist

without contrast. On the one side is light on the other side dark and both are

equally important. That might sound childishly simple and I suppose it is. But

that is the way we look at paintings, that is the reality, and anything that is

tenuously complex is not the reality.

Urban futures

are all saying that in their various ways. Perhaps the prototype is Jean-Luc

Godard’s Alphaville (1965), set in a nightmarish Paris.

The myth (Lemmy

Caution) conquers Alpha-60 and the same is possible with E=MC². We don’t have

to slavishly follow the light equation, or live in “lightspace”. We can take

back the world of geometry which in fact is composed equally of darkness. That

is the land of irresolvable myths. Godard has this logical tyranny running

through the imagery, at one point E=MC² flashing onscreen (about 18 minutes in when Caution visits the dive his pal Henri is staying, going up the stairs, also with Fifi a few minutes later, later on when Alpha-60 is breaking down).

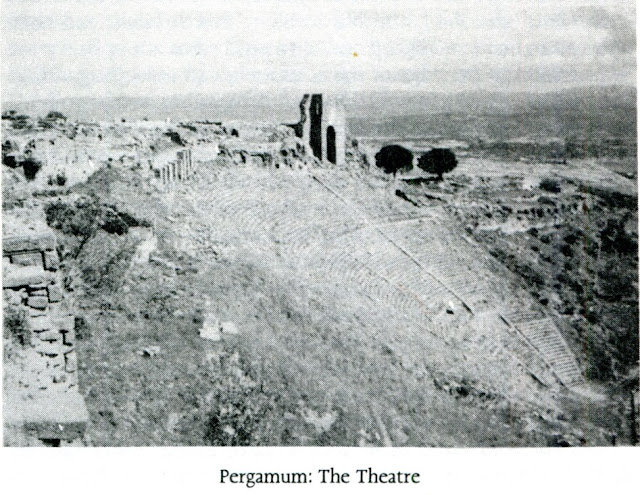

With a bit of

imagination, the vistas of a romantic ruin can draw us back in time. The

monumental qualities of stone, etched against Mediterranean sky, the heroic

aspect of a theatre. The fantastical geometry and geography are pinpointed by

the play of black on white, giving a graphical quality that is overwhelming in

its simplicity. As we sit on the top tier of the theatre, shadows gradually

lengthen and our mind is transported back to the ancient clamour of performance

and ritual..

Though the

theatre was large, and could accommodate an audience of no less than 15,000

people, the lie of the land made it impossible to complete the semi-circle as

in most Greek theatres.. But this was compensated for by the superb view in

front of the spectators, looking out across the valley and fertile plain to the

sea and to Lesbian Sappho’s island floating in the bay. In the evening the warm

air would rise from below, and in a gentle breeze, carry every word from the

stage up to the furthest corners of the auditorium.

Duncan Forbes,

Travels in Turkey, The Book Guild, 1987

The simple

dominance of ancient sites is a “good tradition”, bounded by time and

geographical space. The rain may fall, but we still feel safe inside. Was

this yesterday? Yes, because time is flowing through the ancient stones.

Forbes’s book

has a conversational, documentary quality. The pictorial aspect of things is a

very accurate representation of their aspect in time and place. Almost

Tintinesque. The graphical quality of stone and earth when limned, etched

against Mediterranean light. The graphic and theatrical are actually reality

and not the purely logical theory or ideology. Along with “lightspace”, we also

do not live in global-space or technocratic-space. They are just inventions of

a logical maze.

Alphaville, the light equation, the logical maze..

Without the shadowland there is no romantic decadence, no decay of light. The

twilight in an oasis with camels slaking their thirst in the frond-fringed

atmosphere.

You can’t

imagine a desert without an oasis, or an oasis without a caravanserai. It’s a

good tradition and traditions travel the fertile paths of Man. But fertility is

simply the absence of light. Ancient traditions are well aware of this fact and

there is no escaping it.

The way out of

the uncomfortable logical maze is mainly to be much more traditional, since

traditions exist in the scenic land of time and place. In Travels in Turkey

, written in the 80s, people still used donkeys, the simpler rhythms that are

tied to the land. The book is good at evoking the sense of a continual history

- Greek, Biblical, Ottoman, Christian - tied together by geography.

There is a sense

in which ancient traditions – whether Biblical, Greek, Medieval – are tied to

geography, and the simple drama of line drawings. Europe is tied to geography,

basically, not politics.

*If you’re out there Perrine, I need someone

to write French links to French pop-culture types, sort of PR.

The general drift is rebellion, a revival of l’esprit

de Monterey et ’68. Le deja-vu, c’est nous.